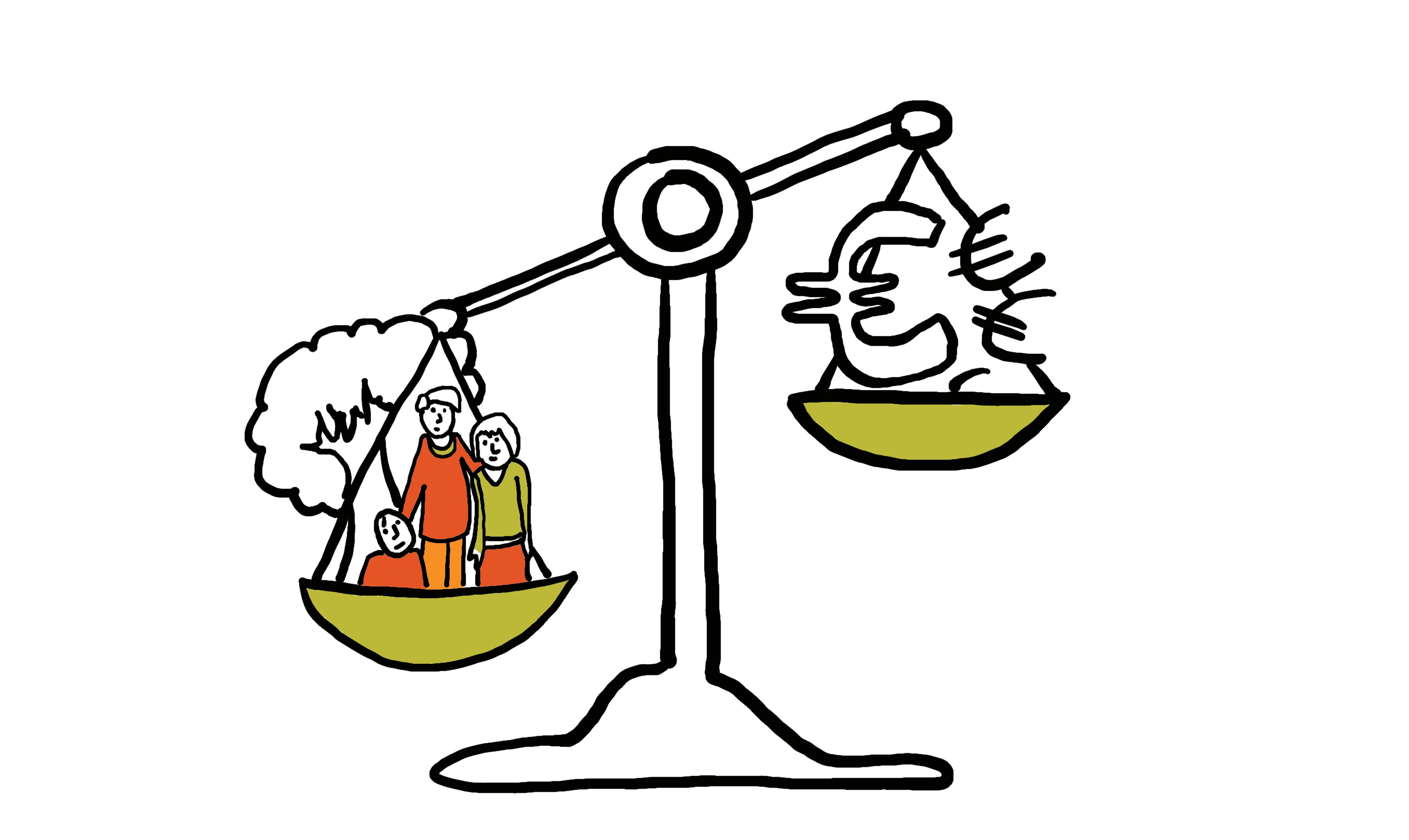

Change in value definition

- from financial cost & benefit to societal added value

Circular and reversible building solutions are often perceived as too expensive compared to the conventional solutions, which have been optimised for decades. This reflects a short-term perspective, in which the financial investment cost is considered a principal decision criterion, not looking at potential financial gains and the individual or societal added value that circular and reversible building solutions could deliver over their entire service life. Having a great impact on the environment and society, the current building industry needs innovative business and financial models with a long-term perspective.

Current ‘one-time sales’ mechanisms are already challenged with ‘long-term service agreements’, in which building products can be used and reused within the built environment or repurposed for alternative applications. Such circular business models provide a continuous revenue stream for the producer, while improving affordability for the end user.

What is the reward in the long term?

- A non-amortised building stock. By making building components reusable and buildings adaptable, their value is better conserved through time, strengthening the business case for long-term investors.

- Buildings that have an overall positive impact. By balancing long-term financial, environmental and social value with short-term investments, we aim to create buildings that are affordable (for the building client, users, as well as building professionals), lead to zero construction and demolition waste, produce energy, purify water and air, and make management of future transformations easy.

- Safeguarding the future use of Earth’s resources for the next generations through business development. Knowing that cities, buildings and building products only make temporary use of (critical) materials, water, energy and land, business developers will create alternatives to the dominant ‘sell-own’ model, through which they provide services instead of products and recover resources for the next service.

Why isn’t it so easy to initiate change today?

- There is a lack of overall management and monitoring related to the use of resources in view of fair access and affordability for all. Without any control, large private companies could have a monopoly on certain product services, increasing the risk for price-fixing and the supply of inferior products/services, losing any incentive to innovate.

- In some EU countries, such as Belgium, private ownership of houses is financially stimulated by the government, as a kind of pension/retirement investment plan.

- There is a lack of judicial assistance and policy regulation to initiate circular product service systems. It is often unclear how responsibilities should be shared between users and service providers.

- There is a lack of knowledge and expertise on circular business models within the built environment. Although there are already some some success stories using circular business models, such as product service systems, experiences within the built environment are still limited.

- Leaving ownership of building products/systems to the manufacturer or supplier might require major upfront capital financing, as the investment is only paid back during the use period (or even only in a second or third use cycle) and not before. Convincing financial institutions to provide financial capital might be difficult due to inherent uncertainties related to the return on investment (period).

- Lack of decision-making support to take into account financial costs/gains, societal impacts/benefits and added value/burden for the end users regarding the life cycle of (circular and reversible) building (product) solutions.

Which actions are needed?

(L = long-term perspective; S = short-term perspective; B = within the BAMB project)

- Internalization of external environmental and social costs and benefits in prices of building (product) solutions (L) is an effective instrument to sensitize stakeholders– in particular (end) users – of the potential (long-term) societal impacts. Internalization of external costs will only work if it is applied over country borders (to avoid economic trade-offs). Taking into account of external environmental and social costs and benefits of products and services should be thestandard within public procurement of infrastructure and (public) buildings across the EU (S). This is already the case in the Netherlands, where public procurement rules for ground, road and water infrastructure is based among others on life cycle costing and external environmental costing. This kind of practices could be used as a stepping stone to internalise external costs also in the private sector.

- In anticipation of positive market mechanisms based on internalization of external costs, designers, project developers, facility managers, service suppliers and (end) users need to be supported in their decision-making through integrated assessment models and instruments (B–S). Within these, initial costs and benefits of (reversible and circular) building solutions are compared with potential life cycle gains/burdens.

- The development of a ‘one-stop-shop’ framework for circular business models (S) will help frontrunner business developers, within the entire value network, and end users to consider financial, social and environmental value creation through different kinds of product service systems and different contexts. Mainstream implementation of circular business models is expected on the longer term (L).

- Experimenting with clustering of roles within the value network (S) to create new added value and manage risks in an effective way when upscaling product services to a building stock level. Examples of role clustering are: (1) citizens cooperatives financing each other’s dwelling, (2) a circular economy service company (CESCO) combining asset management, monitoring of building and building product performance, ownership and financing of the building

- Experimenting with the use of integrated decision-making and circular business modelling needs to be done in pilot projects (B–S). Not only will these practical experiments provide the necessary proof-of-concept(s), but also provide feedback to prepare these instruments for broader use.

- In order to stimulate the uptake of circular and reversible building solutions with long-term societal benefits, different target groups need to be sensitized (S) on the potential benefits and drawbacks these solutions could provide them. The type of knowledge exchange can be tailored according to the target group: information campaigns, websites, books, network events…

- Different business and financial incentives (S–L) need to be created in order to motivate all stakeholders within the value network to embrace circular economy concepts and strategies. For example, architects will more easily take up reversible building design if being financially remunerated for providing (design) counselling to building clients for future transformations. On the other hand, building clients and real estate owners will be more inclined to invest in change supporting and circular building solutions if the economic value of the building is maximally conserved. Especially for buildings with a short transformation cycle (such as stores, offices, sport and leisure infrastructure), the financial investment of adaptable and multi-use building solutions will be returned more easily. Advantageous loans (comparable with ‘green loans’) will provide some extra financial support.

- Through public procurement (S–L) change supporting and circular building solutions used for and within (new and existing) public buildings can inspire building professionals and project developers to do so as well.

- Lighthouse projects need to be set up (S), i.e. large scale demonstration and ‘first-of-its-kind’ projects, in which additive manufacturing and open building systems are combined for change-supporting and circular buildings. The scale of these projects will support experiments with circular business models and upfront capital costing.

Back to “Building as Material Banks: a vision”